“While I love Buddy (Guy) and B.B. (King), I can’t see them doing ‘I’m Not in Kansas Anymore,'” says Joe Louis Walker, “but I can do it and pull it off.”

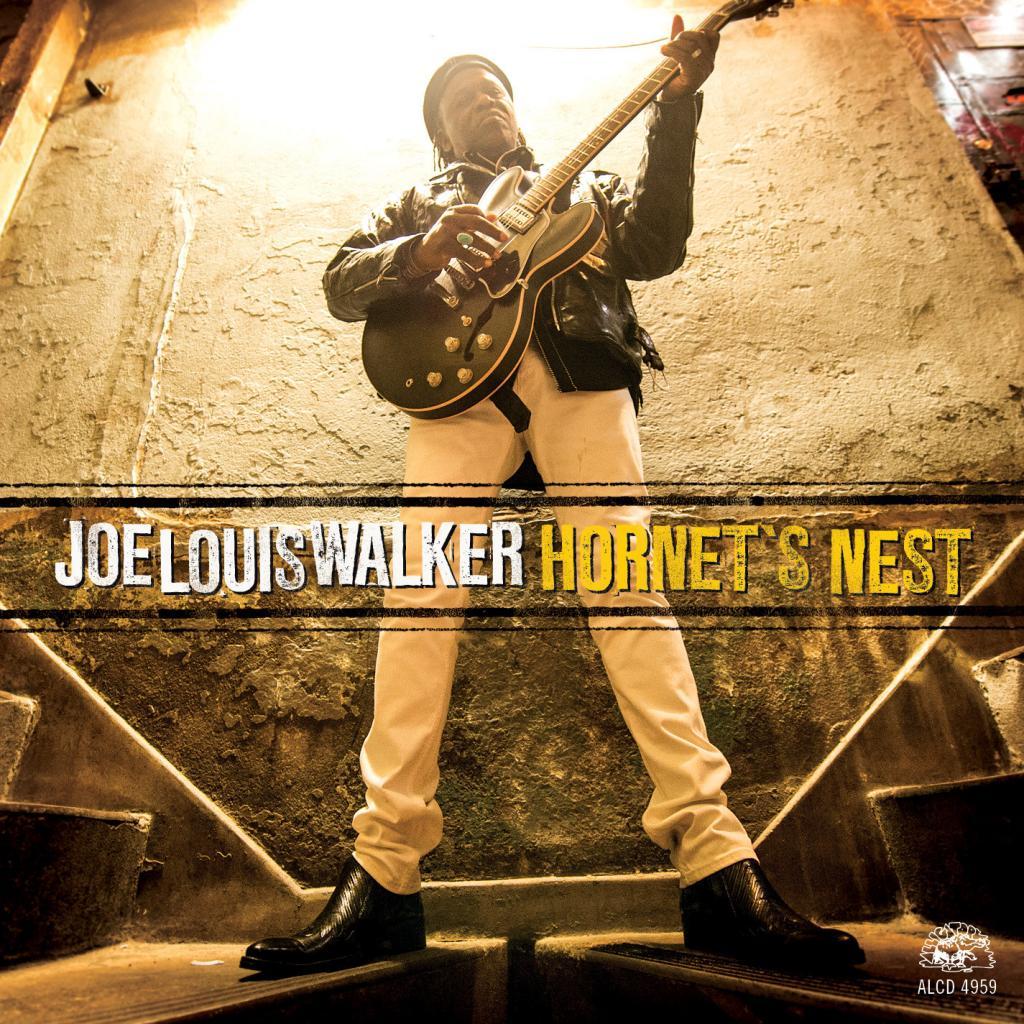

One of 12 songs on Hornet’s Nest, Walker’s second album for Alligator Records, “I’m Not in Kansas Anymore” sounds like The Who jamming with Cheap Trick. It’s sequenced right after “I’m Gonna Walk Outside,” a slide guitar tour de force that would fit right at home on Muddy Waters’ Real Folk Blues album from the early ’60s. And it’s followed by “Keep The Faith,” a gospel song in the Five Blind Boys of Alabama tradition.

Walker calls himself a musical chameleon, and this album certainly confirms the self-imposed title. “I’m all over the place. When I used to try to learn how to write songs, Willie Dixon would tell me, ‘Joe, we gotta find your style. I know your style. It’s all over the place, but it’s first you. It suits you because you just do it. You do it because that’s who you are, and it comes through, and I like to think that’s what it’s about.'”

Each of the three songs mentioned above was written or co-written by producer Tom Hambridge, who also produced Hellfire, Walker’s 2012 Alligator label debut which earned the Living Blues Critics Award for Album of The Year.

Walker says the songs on Hellfire were written in the studio in three days, and that he had a raging ear infection when they recorded it. He hired Hambridge to produce Hellfire and then sold the finished product to Alligator, securing a three-record deal in the process. Hambridge rightfully has garnered a position just under that of T Bone Burnett as the hot blues producer for his defining last three Buddy Guy albums, the Grammy-nominated Cotton Mouth Man CD that’s earned James Cotton a Grammy nomination and for work with Derek Trucks.

Hambridge has an uncanny ability to bring the artist’s personality into sharp focus with his skills that include co-writing and drumming. Joe Louis Walker’s talents are extremely eclectic and include incendiary guitar work, unique and varied vocals and arrangements on the title cut “Hornet’s Nest,” “Stick A Fork in Me,” and “All I Want to Do” that stir into cruising firecrackers that cross over between blues and rock without ever denying Walker’s street creds or his blues authenticity’

Walker quotes Robert Jr. Lockwood as saying, ‘Joe, you’re a smarter guitar player than you act.’ Walker translates the iconic blues and jazz guitarist’s comments. “By that he sort of meant that you can play whatever you want to play. Don’t listen to other outside influences. Listen to what you do good. And if it’s good, do it.”

In picking a producer, Walker looks for someone who gives him the space to stretch. “A lot of (record labels in my career) passed because I wasn’t a one-trick pony, and a couple of ’em said, ‘We’ll do you a contract, but we want you to just grind the blues out.’ I think an English company told me, ‘Just grind the blues out.’ Then a Dutch company told me, ‘Just give me at least four slow blues, Joe.’

“I prefer a guy like [Steve] Cropper who says, ‘Ok, try it,’ and they say, ‘You might not want to do that, but go ahead and try it anyway, and if you miss the mark, ok. It sounds like you mean it.’ Bruce Bromberg (at Hightone Records) did that. Cropper did it. So they let it on the record, and it ended up being one of the most incendiary things whereas if you never get a chance to try it, you don’t know. You always stumble upon things, and Tom is like that except Tom by him being a singing drummer and songwriter, he can write stuff for you. He’s got you in mind. And when I got together with him the first time for Hellfire we pretty much wrote 13 songs in two days.”

One of the cuts on Hornet’s Nest, “Ride On, Baby,” is a Jagger/Richards song from their 1966 album Flowers. “I asked Mick. I said, ‘Man, I want to do “Ride On, Baby.”‘ He said, ‘Well, you should do it then. I’ll sing you the lyrics.’

“When you listen to the original version, Mick and Keith’s version is a little faster. That song put me in the mind of some of the songs that Mick and Keith did like ‘Under My Thumb,’ ‘Out of Time.’ I think ‘Out of Time’ is on the other side of Flowers, and when I heard that, it put me in the mood of that, but it was like it sort of got a little classical piano, but I think they used a harpsichord on it. When Reese Wynans put the classical sort of piano thing in it, and we put the soul thing up under it and me and Tom singing harmony on it together, it really worked.”

Listening to Hornet’s Nest, one can’t help thinking that somewhere between these two Alligator albums, Walker and the Stones passed each other at the crossroads, that as he gets hotter at their game, they get colder – at least when it comes to new material.

In their defense, he says, “You can’t wear the same mantle you wore when you were 21 when you’re 61 or 71. It’s sort of hard to do. The music industry itself has changed. and you have all the young people coming in trying to wear that mantel, and it’s one of their bugaboos, especially for a songwriter or a songwriting team to write a song that’s gonna get a 19-year-old all jacked up like you get ’em jacked up on ‘Satisfaction.’

“I mean how many cats can say they wanna see this chick, and she’s on a losing streak. You don’t have that problem anymore when any chick in the world would be with you. So I sort of put myself in that position. When you go see ’em, everybody wants to hear the older songs and the newer songs? How do you compete with the past like that?

I ask Walker if he thinks if he’d been as successful as they were early on, would he be able to pull off a song like “Hornet’s Nest” or “Stick A Fork in Me” at age 64?

“Well, I am. I’m pulling it off,” he says.

And he is. How come?

“Well, I guess because I’ve yet to be knighted Sir Joe,” he says, laughing. “I don’t have a book called Life (Keith Richards autobiography) where I’m just ragging on my songwriting partner. I believe really in my heart some of the controversy with guys like that. I won’t say that it’s part of their aura, but I think in a way it is. What people like about ’em – to give you an example, I went and seem them last year in DC. I went up there with Ronnie and seen the last show.

“The very first note none of ’em started at the same time. They had to stop the show. They stopped the show, and the people gave them a standing ovation because that’s the Rolling Stones we like. In other words, they fell down on the first freaking bar, but it was so cool. That is the Rolling Stones that we like. They’re human. And they put all that human shit out in the public eye, and that’s great ’cause nobody wants anybody perfect. And that’s what we like about them.”

Walker credits Branford Marsalis with explaining another reason The Stones sell so many more records than he does. “Like Branford Marsalis told me, he says, ‘Joe, if you’re on the curve with everybody else, you’d probably sell a lot more records, but if you’re ahead of the curve, you’re not gonna sell a lot of records unless people catch up with you, or even singing a simple song.’

“So I try and do both. I don’t want to get esoteric. and I don’t want to get too brainy, and I don’t want to be too roadhouse. I want be who I am, but I want people to know if 40 years from now you put on 20 blues records, you put mine on, it’s gonna sound a little bit different, and the minute I open my mouth, you’re gonna know it’s me, and I think I’ve gotten to that to a degree.”

Walker started his career at 16 in the Fillmore District of San Francisco. “I came out of the San Francisco Bay area where they had blues and funk. Then all the younger blues guys came, and then the hippy music, and all those people were my friends, and some of my contemporaries. So I’d come up out of a thing that was all different styles of music.

“I lived in Chicago, but I didn’t stay there long enough to be a straight 12-bar guy, and there’s nothing wrong with that. My dad provided the template: T Bone Walker, Mead Lux Lewis. He said, ‘Listen to the guy who lived down the way from me, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, all those cats from Arkansas and Mississippi.’ I listened to the real stuff before I heard all the other stuff”

The Fillmore District in the mid-60s went from being an African American neighborhood to being a hippy enclave. Walker fit into both of those camps. “It was easier for me than it was for someone like my dad. He was from Greenwood, Mississippi, and he came out with a family like the Clampetts (of the Beverly Hillbillies TV show) basically, like The Grapes of Wrath.

“I mean literally, that’s how my dad and them came out, nine brothers and sisters, great grandmothers and grandmothers, but the neighborhood was pretty much accepting. It wasn’t growing pains where people had to get used to being in close proximity to people. To be quite honest, the powers that be, the city hall and the governor of California, they didn’t have much time for people from my neighborhood.

“People all who were trust fund babies would come out and all the musicians from the West Coast, the mid-west and the east ’cause it was such bad weather, and you couldn’t let your hair down. Then everything was polarized back in the east. You got to California and San Francisco, and you could walk in any part of San Francisco and you still can do it. There ain’t no area where you can’t walk.

“So there was that tolerance and not to mention a district for gay people, The Mission District for Hispanics, but everybody mingled together, and the music was the conduit for it, and the freedom to play the kind of music you want. So it was tailor made for me because I got along basically with everybody. I grew up in a tolerant city.”

From 1975 to ’85 Walker was in the gospel group The Spiritual Corinthians. “To be honest, I’m not 100% a blues guy. I feel like this. I can take music and mix any kind of music I want as long as there are two kinds, good and bad. And as long as I’m doing what I’m doing, I’m not pandering. That’s where I am with it. I’ve always been there with it, and there’s guys that can straddle that fence like Otis Clay, and there’s women that can straddle like Mavis Staples who really have a solid footing in gospel, but I would hazard to say neither one of those people are super religious Bible thumping.

“I don’t equate Mavis with Shirley Caesar, and I don’t equate Otis Clay with someone like Claude Caesar. I consider them a branch of that tree, but they are smart enough to move on with the music, to draw more people in and like Mavis said, ‘What are you doing playing the devil’s music?’ She said, ‘I didn’t know the devil had any music.’ Well, neither do I. I don’t know the devil had any music.

“In the Bible it says make a joyful noise under God. As long as you’re making a joyful noise, that’s what music is all about, you know, redemption, a way to bring people together, a way to connect with people about what it is that we can all survive hard times or share good times or shared experience. I think that’s what it’s about.

“The reason I like Fred McDowell and I got along with Fred McDowell as a youngster is because he came out of the church. We could sit and talk about stuff like that, and he couldn’t do that with all his minders and handlers, because they were young suburban kids, but he could talk to me like that, and so I seen Fred wasn’t as torn as someone like Son House about that issue, but you can hear it. You can see it in Kinescopes with Son House when he’s talking about it.”

Since 1985, Walker has been making eclectic albums that roughly fall under the genre of blues. But he shares a bond with the Rolling Stones. “When they came to the United States they were treated like the people they loved in the music because they had long hair.

“A lot of people don’t know the vitriol with which they were treated in places like Arkansas and places like that. You read Keith’s book and you’ll see he’ll say, ‘Well, at the end of the show we’d go with some of Tina Turner’s background singers. We’d go on the other side of the tracks and we were just accepted wholeheartedly whereas when they came – they caught hell.’

“And like Mick says now, the band they love to hate, now people love us, but – and it’s so of funny, but, yeah, I don’t think anybody who came up through music in my generation or the generation before me like Bloomfield, those before him like Buddy Guy where the Stones’ impact and what they stood for did not affect everybody (the way it does today).