Martin Lang’s song “Reefer Head Man” on his new album Bad Man on Random Chance Records in many ways is his “Satisfaction,” The Rolling Stones’ first high-charting single. Andrew Loog Oldham told the Rolling Stones in 1964 that if they didn’t start writing their own songs, they’d be relegated to playing British nightclubs for the rest of their career, however short that might be.

Like the Stones in 1964, Martin walks a tightrope between two cultures: African American blues and white rock and roll. He’s a highly educated white man who has spent a quarter century playing Chicago West Side black clubs, doing session work for Chicago’s most indigenous label, Delmark, and more recently recording albums under his own name for Rick Congress who positions his Random Chance record label as offering “blues, jazz and whatever.”

“Satisfaction” elevated “Britain’s newest hitmakers,” advancing them from an electric blues cover band to a style that set the stage for “rock” replacing “rock and roll.” Instrumentally, it broke through the barriers that had defined postwar blues to that point, and lyrically it addressed adolescent sexual frustrations at a time when the youth rebellion against parental Puritan mores was emerging worldwide.

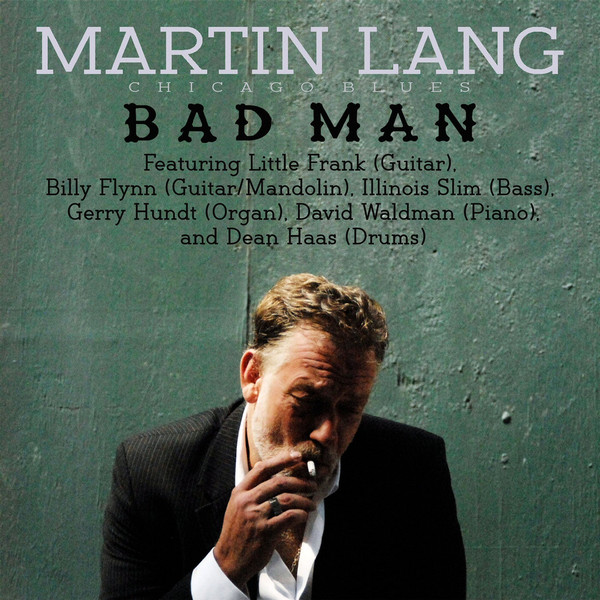

Label owner Rick Congress was right in pushing Martin to do his own songs on his own album because a lot of the stuff on this release – and less so on his other two solo albums – can be taken on two levels. On one level “Reefer Head Man” is a tongue in cheek novelty with lyrics about a musician who smokes dope all day long. The song concludes with Lang coughing profusely. On another level, the arrangement is an authentic West Side ghetto blues. Martin is a 25-year veteran of the West Side sound, has played and recorded with scores of Chicago blues veterans and has released an album produced by Dick Shurman, arguably the most lauded producer of that genre. Bad Man is bad, man: intense, real, authentic and contemporary.

“I’m a guy a lot of people regarded as a real good harmonica player and a real good side man, but am I front man material? I don’t know,” says Martin who is not yet totally comfortable in the role into which Rick Congress has thrust him. The fact that Martin’s a white man living in a totally black world is part of the draw. He went from law student to West Side sideman in one huge cultural leap. He recalls the tipping point when he bailed on law school and made blues performing his only gig.

“I was walking down St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans at 3 o’clock in the morning, walking out of the law school library, and here’s this car pulling up next to me, and it’s my contracts professor. He’s behind the wheel, and he’s got cables and all this shit in the back of the car. He’s coming back from a gig, and he’s hammered. He opens the door and says, ‘Hey, Martin, get in the car.’ So, I get in the car. He says, ‘Where are you coming from?’ I say the library.

“He’s listening to WWOZ, the soul and blues station, and all of a sudden comes this number on the radio that I recorded like five or six years earlier in Chicago, and I say, ‘Hey, professor, that’s me playing that.’ He says ‘That’s you?’ I said yeah. He says, ‘Why the hell are you in law school?’ I went back to the crib, and I couldn’t get that question out of my mind. I pretty much quit after that.”

Playing the West Side as a white man taught Martin about a whole different world.

“In black clubs, there’s call and response feedback on the bandstand between the band and the crowd. They would holler if you fucked up, and they would holler if you did something cool. ‘Man, what the hell was that,’ they would say. (I’d say to myself, ‘Ok, I’m not gonna do that shit two times or play bump chord or some shit.’ If I did something good, they would be clapping and cheering, getting up on the bandstand.

“You gotta prove to them you belong on that bandstand. (At some clubs) we only did three sets, four sets tops, but man, when we were working at The Fish Market or 205, we started at three of four in the afternoon and went until two or three in the morning and played 10 sets.”

Rock audiences are completely different. They’re there to worship. “You don’t have to prove yourself. In 1975 white audiences went to see Jimmy Reed or Howlin’ Wolf, and they’d sing along. When they walked into a blues club, they knew what they were doing. They knew what they wanted. They were in for (a little) danger for the night, hang out with their friends, drink with their friends, flirt a little bit. That’s how it was. It was cool, and blues people really understand the music. Most of those people are gone now of course. Up until the ’70s and ’80s, you could hear blues on the street, Not much the ’90s.” The average blues concert today attracts a mostly white audience with a totally different cultural background than the black artists on the West Side. These white fans are used to idolizing rock stars. “You don’t have to prove yourself to them,” says Martin.

The West Side is the last vestige of what postwar Chicago blues was like in its heyday. Charlie Musselwhite told Lang you had to be there then. Musselwhite recalls a Little Walter gig at a bar on 35th and Indiana in the ’60s. “There was a big old wooden box – a hollow wooden bandstand. They would get going, and it would amplify the beat, and the whole place was like a giant guitar which reverberated, and people would dance. Walter was putting this new sound on them. It was like this hyped-up Muddy Waters.

“Young people would come out and see him, and this whole place would pulse. People would dance. The whole first set was instrumentals. And he would say, ‘Look, I know you just got paid. It’s Saturday night, and I’m begging you to dance.’ He’d make ’em dance. And next to that was a club that Charlie told me in the early ’60s every harp player in Chicago used to hang out there, everyone of them: Big Walter, Little Walter, Louis Meyers, everybody.”

The funniest anecdote from my interview with Martin is not first hand, but I won’t reveal who told him this story. “Every night Little Walter would take a different woman home. ‘Man, I’m gonna see what Walter is doing to them.’ This guy walks down the hallway and goes up to the door, peeps through the key hole, and Walter’s peeping right back through at him. (Laughs) He went back to his room and soon as he closed the door, Walter starts screaming again. So, when he woke up the next morning, he went to get Walter from his room, and he was gone. There was nothing in his room. All the stuff was gone. There was an empty bottle of whiskey on the table, and his footprints were on the ceiling.”

The instrumentals on Bad Man featuring Martin on harp are at times laconic, displaying a studied insouciance, an almost blasé casualness — a free and easy approach that actually isn’t casual at all. After all here’s guy who was Delmark’s go-to studio harpist whose credits are a who’s who of Chicago blues legacy acts including studio work with Tail Dragger (James Yancey Jones), Dave Myers, Jimmy Burns, Willie Smith, Rockin’ Johnny Burgin, six years playing with Dave Myers, plus U.S. and European tours with Pinetop Perkins, Robert Lockwood Jr., Sam Lay and Louis Myers.

Rick Congress basically came to Martin and told him it was HIS time. “Yeah, he said to me, ‘You have to start writing stuff if you want to make another record,’ and I did want to make another record, and I had ‘Younger Days’ and a couple of other tunes like ‘He Don’t Love You’ which is perfect for my vocal range. He really believes in the record, and if I write my own songs, I’ll be the next Tom Waits or something.”

Bad Man producer Dick Shurman gave him confidence. “If the definition of producer means he helps the artist produce, he definitely is that. What he said essentially is, ‘Hey, man. I know you’re a great player, and I’m here to help you achieve that. I know you can do it. I know you’re maybe not sure you can do it, but I am.’”

The title cut is about 1950s western heroes like Paladin in Have Gun, Will Travel who had a high kill count but could quote Shakespeare to the women he wooed.“It’s a theme about TV cowboys, and it’s kind of a gag, you know? I’m taking things on a lot of different levels. People don’t really know me, but people who do, I’ve heard that moniker.”

“Stacy’s on My Feet” is an homage to guitarist Eddie Taylor Jr. who died in 2019 at the age of 43.

“Eddie was a guy I was very close to. I was harp player on his first album (Lookin’ for Trouble 1998). We were like brothers. I would go to his place. We were friends as soon as we met. He had to go (through hell) to get me on his first record on Wolf Records. (They) were bitching against any white kid playing on there, but when I showed up at the studio, I was scared shitless, man, because Johnny B. Moore was on guitar. They had Jimmy Taylor on bass. Eddie was playing lead guitar, and I was the only white guy on the session. I walked in, and now I’m a member of (the) Wolf family. I’m one of the first guys they call, and I know the whole family, me and Eddy.”

Martin recalls a 12-week tour of Europe with Eddie, Tail Dragger and Lurrie Bell with Willie Hayes on drums. It was in Amsterdam when things got rough. “Eddie got really pissed. He hands over the mike and looks around to the band and says, ‘All you motherfuckers, get off the stage. Not you, Martin. You stay.’ So, we did the rest of the (tour) as a two-piece, and we did “Bad Boy.” Me and him are there on this bandstand alone. We are a couple of bad boys in your town a long way from home, and it’s some of the most beautiful harp I’ve ever played. I was so shocked when I heard he died. He died in church. He was playing guitar, you know.”

You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime you just might find you get what you need.