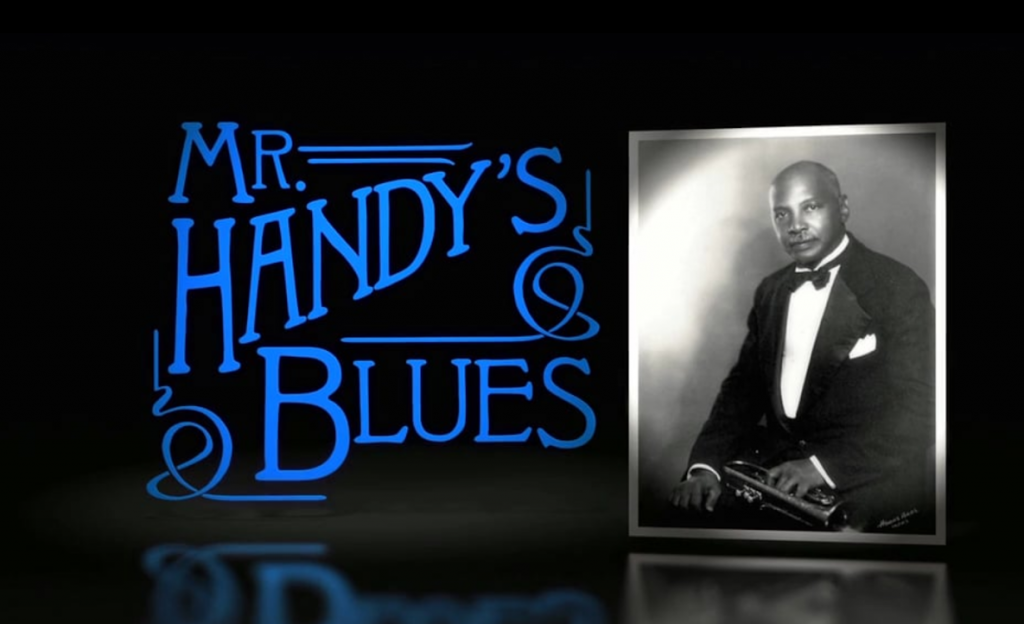

Mr. Handy’s Blues is the never before told saga of W.C. Handy, or the Father of the Blues as he is affectionately known all over the world; it is also the brainchild of Emmy-winning producer Joanne Fish. The producer/director has worked in film and television for 30 plus years. Her work has been seen on History Channel, A&E, Lifetime, CBS, NBC, CMT, etc.

With a predilection for both history and roots music, Joanne naturally gravitates toward musicians who blazed their own trail and opened doors for other artists. Her last independent documentary was called The Sweet Lady with the Nasty Voice, a behind-the-scenes look at life on tour with Wanda Jackson. Just as Handy was the Father of the Blues, Jackson was the Queen of Rockabilly.

W.C. Handy was born seven years after the Civil War to former slaves — a life fraught with hardships as he endured so many years of violent racism, extreme poverty, and disapproval. His father once told him he would rather visit his grave than witness him play an instrument, “the plaything of the devil.” But Handy was hell-bent and triumph-bound. St. Louis was the place he would spend too many days homeless under a bridge, contemplating suicide; and “St. Louis Blues,” written in 1914, would become his magnum opus. The song became a worldwide phenomenon and the most recorded song of the first half of the 20th Century.

Ten years in the making, this film achieves exactly what Joanne originally set out for: to find “that one thread that runs through somebody’s life that explains how they got this level of success,” as she puts it. She hopes that this film will spark curiosity and cultivate knowledge, because Handy’s legacy is sadly fading away. Interviewees of Mr. Handy’s Blues include Bobby Rush, Taj Mahal, the late Gip Gibson, and more. The director’s cut with more performances is available on DVD internationally.

What drew you to the history of W.C. Handy to begin with?

I’m interested in roots, the history of music. My last film was called ‘The Sweet Lady With the Nasty Voice’ about Wanda Jackson, who was a real pioneer of — she went from country music to the newfangled rockabilly, which then morphed into rock and roll. I decided to go back further and explore the roots of the blues. It’s a rabbit hole when you go down it.

It’s a never-ending story. You know from being on a magazine that features blues. When I got back as far as W.C. Handy, I thought that was something I could really sink my teeth into, because it’s such a positive story. It doesn’t sound like the usual blues story, because he was born 40 years before all of that history started. It’s interesting to me to see how he achieved such great success and great notoriety. He’s still revered all around the world, so that’s what got me going.

Can you tell me about the research, the interviews, how it all came together… What are some highlights?

A highlight for me was finally finding somebody who actually knew a lot about Handy. There’s a lot of researchers out there. The only book about Handy was a book written by Handy. It was his story, but it was kind of more colorful and written in a language that wasn’t easy to cipher.

He was very eloquent.

Yes, and it’s very colorful and flowery language and really neat. But it wasn’t like — what were the facts? Exactly where were you at that time? So, that took a long time. What surprised me the most was when I first went to Handy’s home, I thought, “Well, I know any minute now I’m going to find out there’s a huge documentary about him.” I happened to be in his hometown for another film festival at the time for my last film. I went to the museum and thought I’d find out somebody has already got the jump on this or it’s been done. The more I dug, no one has ever done this. No one has even written a book about him.

That makes it all the more interesting.

Yeah. So then you think, well, why not me?

I was kind of blown away. There’s a lot to know about this guy.

Yeah, a lot of history. Some people said, “You can’t do it, because you have to tell the whole story of the Civil War to figure out exactly where he fits in.” But hopefully people — if people are interested, it’ll spark their interest and they can go back.

Kind of like a Ken Burns documentary.

Yeah, it’s kind of like that. I’ve done a lot of biographies for television networks, for A&E Biography and Lifetime and the History Channel. And that’s how I spent my whole career was working in L.A. in the television business. And then I lived in Nashville for a while and did a lot of biographies of country music people.

Who are some country artists you’ve worked with?

Well, I did things like ‘100 Greatest Songs of Country Music’ and ’50 Greatest Women of Country Music’ and ’50 Greatest Men of Country Music.’ And then I did shows on Toby Keith, Kenny Chesney, the band Alabama, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, George Jones…

George Jones is my favorite. Favorite of all time.

I mean, he is the sweetest guy.

I named my first goldfish George Jones when I was five.

Did you really? He is just…

I love him so much. I have a George Jones tattoo.

So, you know he’s just the best. I did a music video for him, a song called “I Don’t Need Your Rocking Chair.”

Yes! I love that song.

It won Vocal Event of the Year at the CMAs.

(Fun fact: Nancy Jones accepted it on his behalf since he was in the bathroom.)

You did that video!

Yes, with George Foreman. And we got a boxing ring.

I remember that! So, you produced that video.

Yes, when I lived in Nashville.

That’s amazing. I’m so glad I asked you. See, you and I speak the same language. Don’t put an artist in a box. It all goes back. Country, blues, rock and roll. It’s all roots.

Yeah, and it should be looked at that way, like it’s a tree and there’s all the roots.

I like the concepts within this film — interstices of very talented musicians playing W.C. Handy songs between interviews, archival footage of Louis Armstrong and George Gershwin paying homage, recordings of Handy speaking to Alan Lomax…

I didn’t want to use a narrator, so I had to use the old timey silent movie screens.

It added a very nice touch to the film throughout.

I appreciate that. I really avoid having a narrator. And I had the luxury of having Handy’s voice. I tried. You know, after years of writing narration for people to come in and do, it’s like, “If you just do it first person, it would be amazing.” And since Handy’s been gone for so long, let’s bring him to life a little more. So having those recordings was a godsend.

They’re very clear, too.

Yes. He has a great voice. And he sings and it’s so cute.

He didn’t really have a speaking voice like you’re used to hearing blues singers. He had a very unique voice and diction.

Yes, he did. And kind of a higher voice.

I like how the film always came back to his fortitude as the reason he overcame hardships and what made him stand out as a musician of substance. He was the first to publish music in the blues form. I think he kind of changed the landscape. There’s a poetic quality to the kind of musician he was.

Yeah, it’s really — that era. Most of the musicians were minstrels or traveling around. A lot of it is not in the film where he was physically threatened during the minstrel period, and he had to have a gun hidden on the train. And it was a means to an end for him.

I think he just walked that line between being treated like a second-class citizen sometimes, but I’m confident and strong enough in my spirit that I can overcome it. Deal with it now, but I’m going to get past it. He never gave up, because he believed in himself so much. That’s something that everybody goes through, that they need to dig deep. And he had to walk that line between being black in a white world and not thinking of himself as subservient.

And he was able to reclaim his publishing rights, which I thought was very ahead of his time.

He was. He was ahead of his time. I think somebody says, “He was kind of a visionary, a prophet,” they said. Going to his home — it’s a little cabin in Florence, Alabama. It doesn’t take long to go through, but you go, “Oh, my gosh. This is such a positive story.” Everybody could feel good watching this.

Yeah, I feel inspired by him. I kind of drew parallels with him and Tom Petty. The way he was able to reclaim publishing rights, his fortitude, and the way his father didn’t show support for him until he was famous. The true measure success is also about never backing down.

Right. Right. His spirit — Wynton Marsalis isn’t in the film, but I did have a long conversation with him about Handy. I said, “Where did he get that strength to keep going?” He said he didn’t know a lot about Handy, but he said his father was a preacher. It was kind of born into him. He wasn’t real religious. He went back to spirituals later in life and arranged them and did a book of Negro spirituals. He wasn’t a regular at church or anything. But that might be the reason.

In all my years of doing biographies I always want to know, you know, what is that thread? Because we’re all born equal. What is that one thread that runs through somebody’s life that explains how they got this level of success? It’s always fascinating and it never gets boring.

I think a lot of the time it’s you have people telling you that you can’t do it.

Yeah, that’s a good one.

Seems to be a catalyst. And I can relate to that.

Yeah, me too.

He’s such a considerable amount of the blues songbook. With that said, why do you think “St. Louis Blues” was regarded as his magnum opus?

That’s a good question. I just think it was a combination of different — it has its fingers in a lot of different types of music, even classical. It just can be translated into so many different genres. And I think, for him, it was a combination of all the things he was working on and putting together and mixing bits of this and bits of that.

And I think that one just struck a chord with people. It’s true that it’s the timing, the way it came out and the way it was presented. With recordings coming out it got spread around more, because before that his songs were just on sheet music and played live. I think the Bessie Smith recording and Louis Armstrong…

I love Ella Fitzgerald’s, too. She did a great rendition. But I think the Bessie Smith clip was my favorite part.

Yeah, that’s really a highlight because we’re lucky we have that. That’s how the word got out. So in France, In Paris, where jazz was starting — and that record came out and people started hearing it played different ways. They thought it was like “The Star-Spangled Banner.” They thought it was America’s anthem.

So I think it was like lightning in a bottle with timing. And he was at a mature level in his career. He was a very good musician who knew how to read and write music for all his musicians. I think it was his — he intended it to be his opus. Putting it all together and putting in the strains of habanera music from Cuba. It’s the first one where he combined all of his musical interests. And one thing that somebody said — and this is really true — in Europe, all the classical composers would take music from folk music where they were from. They all did that and would turn it into these symphonies and these great works of art.

And that’s what Handy was trying to do with the blues: take it from the Delta, take this raw music and turn it into a classic. I think that song was a combination of all his attempts to do that. And he had the fame, so he could basically do whatever he wanted.

Definitely. What is your personal opinion of Handy’s signature on Memphis blues?

Well, he is the father figure. He’s a symbol. The “Father of the Blues” was more of an affectionate nickname for him. He’s the father of the blues because he’s older. He’s like 40 years older than all these guys. He set the tone. And Memphis was the first music capital of the United States. That’s where there were lots of German music societies and a huge black population and the Delta people coming up from Mississippi, and a lot of trained musicians. Music was just happening.

There were lots of ballrooms and lots of things going on. He — introducing a new format while he was there and publishing that first song really solidified Memphis’s reputation as the place to go for music. Luckily, it continued with the blues and they haven’t quite forgotten who started it all, putting that brand on there. They regard him now as the father figure for the whole area. They give him respect. My friends say it doesn’t sound like the blues.

Well, he brought a folk sensibility.

Yes. Yes, he brought it to the masses. He brought it to the mainstream, and it would have gotten there anyway. But he did it.

I think he brought his own unique fusion of folk and blues to a wider audience and earned the title.

He had the initiative and the drive. He staked his name and reputation on it. This is the true American form of music that needs to be recognized as something other than just what they do down there in the mud.

Exactly. How do you think his journey through the Delta, and the sounds he heard along the way — from live music to trains to someone literally playing slide guitar with a knife at the train station — shaped his musical style?

It’s amazing to think that he was 30 years old or so before he ever heard this, even coming from Alabama and traveling all over through St. Louis, all his jobs and everything, that it took him being 30 years old — leading an orchestra in Mississippi. It’s funny. They said he would play at brothels and big ballrooms. His band was a little higher-toned. So I guess in that respect, maybe he never did hear anyone singing on the side of the street. He heard a lot of snippets when he was traveling through Mississippi particularly.

One side note: he had been collecting a lot of things from St. Louis, people on the street and the way they talked, their form of expression, when they spoke. Different dialects in different parts of the country. He had always been interested in that. He would make up songs when he was younger, when he was traveling around. That’s how they told the news. You’d hear — the local news would be someone standing on the corner riffing about it. He was really good at doing that, singing songs like, “Hey, old man…”

Oh yeah, just rapping.

Yeah. So that was white and black people. But when he got to the Delta he felt the really deep African-American roots. He could identify with that. He saw the disconnect with what he was doing with more classical tunes and popular songs of the day, and what he was hearing there. It’s like, that’s where my soul lies and I need to incorporate that into what I’m doing as a professional.

One quote that resonated with me was one from his grandson, in which Carlos said his grandfather “incorporated the musical structure that people could listen to and enjoy.” He defied and broke down genre barriers.

Yeah, he wanted to make it more palatable for a wider audience. He said it was the weirdest music he had ever heard, but he could relate to it.

Why do you think “Jelly Roll” Morton branded Handy as “the stenographer of the blues”? What made him so sorely misinformed?

I guess that he was that kind of that ornery type of guy. It was that period when he made that claim and spoke out so vehemently about it — and everyone else too, by the way. He was kind of on the skids in his career. I mean, I love Jelly Roll Morton. Don’t get me wrong. I wish I could have used some of his piano in the film. He plays Handy songs. He recorded his songs. And they’re beautiful renditions. It’s crazy.

It’s like something out of a movie. Like, this guy can’t be serious.

Right. And that’s why it’s kind of puzzling. From my expert, who I trust 100 percent, he said he was just at that point in his career where he wasn’t getting enough attention. His career was on the wane, because everyone loved Handy and not so much Jelly Roll Morton. I don’t think he had the kind of personality, for whatever reason.

He didn’t ingratiate himself or have a lot of friends. I think that’s what it must be. But he was literally listening to the radio and heard that Ripley’s Believe it or Not show, and it got under his skin. It was an affectionate nickname for Handy because he was so much older than everyone.They called him Daddy of the Blues, and everybody called him Pops or Dad.

It was self-proclaimed, but it doesn’t mean that he was narcissistic. He earned the title.

That’s just how people referred to him, mostly because of his age and because of “St. Louis Blues” and the big songs that came out before that people really grasped onto.

And he brought elements that weren’t there before.

That’s right, and the way that it was on the cusp of early jazz. That’s so interesting. It was just the right place at the right time, and he deserved the respect. But Jelly Roll Morton heard that on the radio, the Father of the Blues and the Father of Jazz. Handy was never called the Father of Jazz. But Ripley, hey, believe it or not, right? He said that, and that got under his skin.

He did have the wherewithal to start writing letters and articles about how it was him, and he spread a lot of spurious rumors. It really was conspiracy theories. He said things about Paul Whiteman. Once he got going, nobody was safe from being accused of thievery by him.

Such libel.

Yeah, and ‘Downbeat’ did go back after they published and made an apology. But it was out there. I don’t think he was the only one that harbored those resentments or thought that Handy was getting too much credit, in my mind because of a silly nickname. But also because of his fame and how he was so well-known, just for being himself and not even for his great playing.

People don’t know what to believe, so rumors are so inflammatory.

Yeah, so you’re going to get a few side eyes, a few glances.

I felt bad for the guy.

I know. I did too. I felt really bad for him. I try not to make it be like Handy could do no wrong.

You were definitely unbiased. I did not get a bias.

Ok, good. I feel like after a while you lose perspective.

No, I think everyone reached the same consensus on their own that he didn’t rip anyone off.

That would be a much more exciting film. But he wouldn’t have gotten that far.

Exactly. But see, that’s another good thing about this documentary is that it will bring to light the truth if there were possibly any detractors left.

I hope so. I hope it does, because — one fella did say it was the most authentic blues documentary he had seen in a while.

I agree.

He’s a deep researcher of all this stuff, so that made me feel good. I thought he was going to be the one who pointed out all my mistakes, all the things I left out.

I loved it.

Good. I’m so happy to hear that. I mean, it’s just something different. I’m going to be taking it on a tour; the film got picked up for a tour. It’s called the Southern Circuit. My circuit is Alabama, Kentucky, and North Carolina. I’m really excited. I hope it’s entertaining, but I think it’s really educational.

Have you ever done a film tour?

No. I’ve done a lot of film festivals with this one and with Wanda Jackson. We went to South by Southwest with that one and so many. Wanted to show that one, because Bruce Springsteen and Elvis Costello are in it. And she’s in it. So I’ve done that, stand up in front of an audience and talk about it, but not where it’s the only film being shown and chosen for a purpose. That’s going to be interesting.

What has this experience taught you?

It took me 10 years to make it. I’m glad it took so much time, because it really settled in. My original idea was the same as it came out. Nothing really changed in between. That’s unusual when you have the time to do something. The more time went by, I realized, I talked to people from day one to the last day 10 years later. And fewer and fewer people had any idea what I was talking about. Oh, you don’t know who W.C. Handy is? Well, here. And people might discover him. His legacy is totally fading away, even in Memphis. People don’t walk the extra block to go see his house at the end of the street, so I hope it fosters more interest in him.

Editor’s note: This feature was originally published in November of 2019. It’s been nearly two years since Joanne’s film tour was canceled on its first day in North Carolina due to the pandemic. However, a recent development has arisen: ‘Mr. Handy’s Blues’ has now been picked up by Films Media Group for worldwide distribution in the educational space.