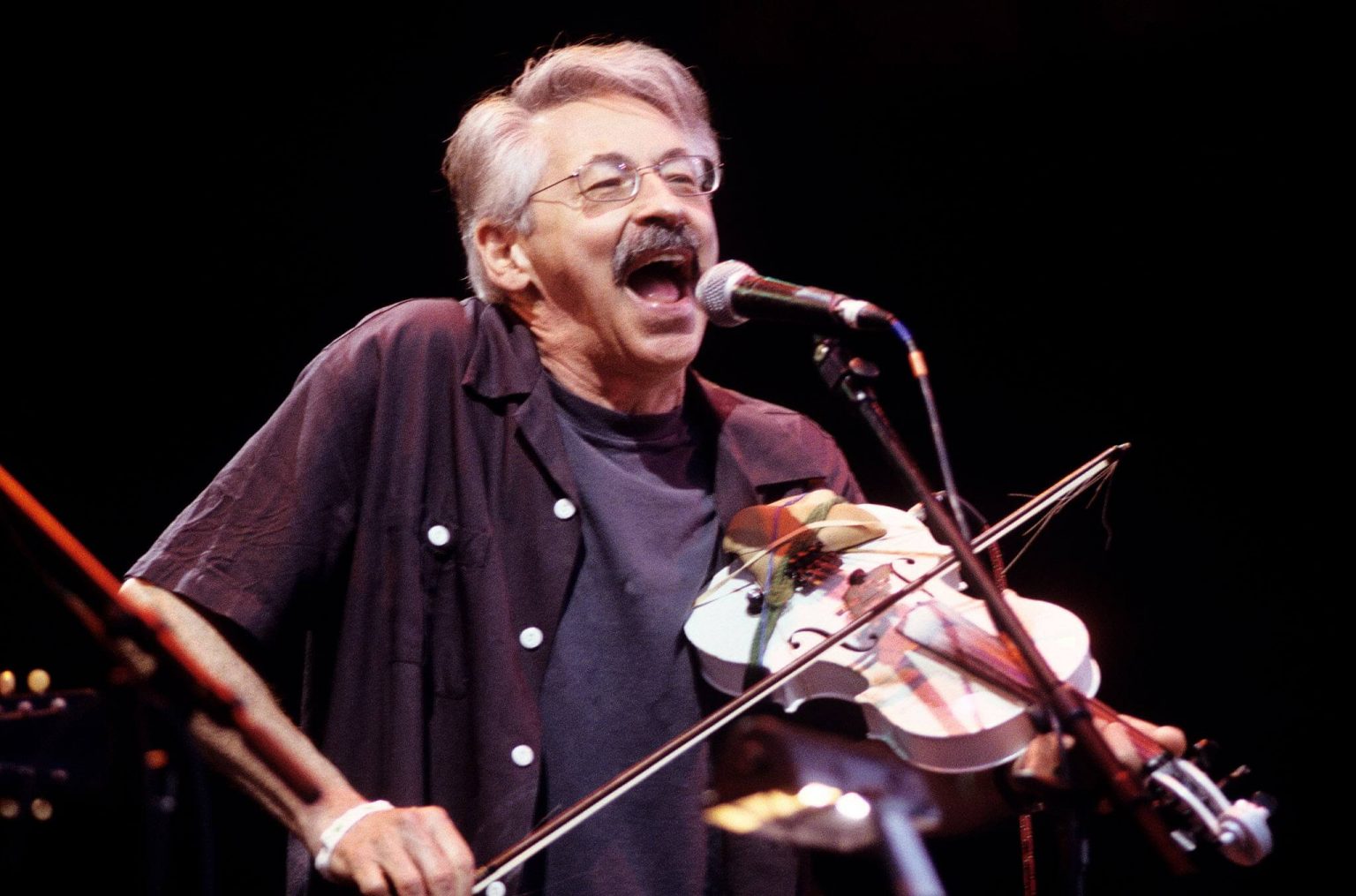

Born into the last decade of the Great American Songbook era, the 1930s, folk subvertist Peter Stampfel considers himself “a lucky son of a bitch.” The fiddle/banjo/guitar player has spent the majority of his life wondering how a certain kind of song can one day waft across the ether only to mysteriously disappear like it never existed. Where did these songs come from, and where did they go?

By way of an answer, Stampfel set out to record his favorite song from every year of the 20th century, 20 years ago. 20th Century, produced by Mark Bingham (Elvis Costello, R.E.M., Hal Willner, Marianne Faithfull) is 100 songs, nearly two decades of record, a century’s worth of music. Some still popular today, some rarities not known outside of aberrant vinyl-collecting completists.

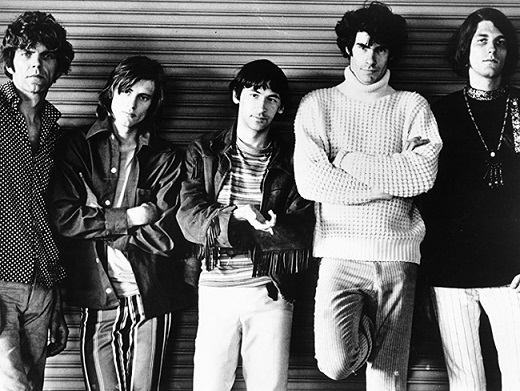

Stampfel has had his six-decade-long career to prepare himself for this endeavor, starting in the 1960s when he would rework songs from the 19th and 20th centuries to adapt to the contemporary vitality of his psychedelic-folk band, the Holy Modal Rounders. Following a chance encounter in a pawn shop involving Stampfel’s hocked fiddle and playwright/actor Sam Shepard looking for a bass player, Shepard joined the Rounders on drums.

Shepard played on 1967’s Indian War Whoop and 1968’s The Moray Eels Eat the Holy Modal Rounders, which featured “If You Want To Be A Bird.” The song landed on the Easy Rider soundtrack, edited by Dennis Hopper into the classic scene with Jack Nicholson riding on the back of a motorcycle donning a football helmet and spreading his arms as wings.

In his Sam Shepard tribute, Stampfel wrote, “It was the ‘Summer of Love,’ which annoyed the hell out of all of us. One July day, I walked into the Moray Eel practice space on East Fourth Street, and there was this nearly bald scary-looking guy pounding away at the drums, his back to me. I thought some local hood had stormed in, and was Sam gonna be mad. But then he turned around, and it was Sam. He had gotten a real short crew cut to protest the Summer of Love. I was calling it the Somber Blub Blub.”

The recording of Peter Stampfel’s 20th Century initially started in 2001 with a core ensemble featuring Amasa Miller from Charmaine Neville’s band, Alex McMurray, Carol Berzas and Jeannie Scofield under the supervision of composer/ guitarist Jonathan Freilich of the New Orleans Klezmer All Stars. Most of the songs from 1901 through 1950 were done over a few week-long sessions at Bingham’s Piety Street Studios in New Orleans.

The last 20 years of the 20th century are not amongst those whose music Peter is most familiar with. In 2016, Peter began soliciting song selections from his many friends who were/are music journalists to cover that era. Mark returned to NYC and recorded Stampfel with pianist Steve Espinola helping out at Restoration Sound in Brooklyn.

On his return to Louisiana, Bingham began recording the Lost Bayou Ramblers at his studio in Henderson, LA. He became the guitarist in the Ramblers side project Michot’s Melody Makers, formed by fiddler/singer Louis, co-founder of LBR. Mark enlisted LBR and MMM bassist Bryan Webre and drummer Kirkland Middleton to record the final songs with plans to finish the project Spring of 2019.

Then Peter came down with dysphonia and his vocal cords didn’t work. He not only couldn’t sing, he couldn’t talk. He spent the next few months re-learning how to sing, using a lower register and less volume. That Fall, while the Lost Bayou Ramblers were on break, Bingham brought Stampfel down to Louisiana, called in Webre, Middleton, and Michot, added Michael Cerveris (star of the Broadway musical adaptation of The Who’s Tommy) and did the last 28 songs.

Mark Bingham was an 18-year-old intern setting up the mics for The Moray Eels Eat the Holy Modal Rounders sessions in 1968. “He was this kid that was setting up the mics and I was constantly stoned on speed for the whole session, but I actually met him again in 1975. And we’ve been friends ever since. I’ve made three albums all together with him.”

20th Century was very much a labor of love for Stampfel and Bingham. “We started recording in ‘02 and finished last October. We did it in different parts of the country, which is one reason it took a long time. Also. It was all self-financed. Between the two of us; our expenses were about $35,000 over the years. Transportation, recording equipment, computer updates. A lot of the songs I had picked out already. There were so many old songs that I loved. Those blanks were filled in pretty easily, but the latter ones I had to do a lot of research.”

In Stampfel’s songs I hear everything from what I call loud folk to jangly pop to traditional bluegrass to punk. As far as eras go, he is most partial to the 1960s. “It was so fucking amazing,” he expresses. “In the ’50s a lot of people talked about this bad new crap — that new crap being rock and roll, as opposed to the good ol’ songs, you know? By the mid-60s, people realized that rock and roll wasn’t crap. But in the ’70s, people started going on about the shitty new stuff. But like I said in the notes from 1970, there was so much stuff that was worth listening to. For the first time, I couldn’t afford to buy all the albums I felt that I had to have.

“People used to throw out old stuff, you know? When I got to New York in 1959, there were so many stories about people finding Tiffany lamps in junk shops, you know? Worth thousands of dollars now. In the 1970s, people started getting into old stuff more. One thing that triggered it was when they tore down Penn Station in New York. I mean, that was like a cultural atrocity to destroy that magnificent structure.”

He posits that we live in a golden age of golden ages, when social media threads are their own literary species. “There are always these jerks that claim that music is crap, as compared to some golden age, which was, you know, like, not now. But the thing is that people started talking about the golden age of television in the early aughties, which was totally accurate. My definition of a golden age is — the number of stuff available is absolutely beyond anyone’s time to watch, eat, or drink, or read.”

Stampfel, who is an associate editor of science fiction publisher DAW Books, says the 1950s was the last time it was possible to actually read all the science fiction books that came out. “And that’s just one genre. I mean, it used to be possible to actually absorb everything that was out in a given artistic field.

20th Century begins with a 1901 parlor song, “I Love You Truly,” and closes out the century with Coldplay’s “Yellow.” The tracklist boasts an eclectic array of songs, including Elvis Costello’s “Girls Talk,” John Anderson’s “Swingin’,” and Curtis Mayfield’s “Momma Didn’t Lie.” He gives a rapturous performance on Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” and on The Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset,” transcending the sounds of hill country in a spirit similar to the Greenbriar Boys. “They’re actually amazing songs. They are. I love going all hillbilly on not hillbilly songs. Did I mention Jo Stafford? There’s a very dramatic, beautiful pop song by Jo Stafford and Red Ingle. They do a Michigan hillbilly song called ‘Tim-Tay-Shun.’ Jo Stafford channels Maybelle Carter. And it blew me away when I first heard it in 1947 or so. It was one of my primary musical influences. It’s where I got going on the great American songbook.”

Stampfel references fake books, which derived from jazz lead sheets used by band conductors. “There’s two basic fake books that were born in 1950. They had about a thousand songs in them, about three per page. I became aware of these books in the ’60s, got my hands on them in 1970 and went through them. And I actually discovered two songs that I hadn’t known when I was a kid. All the other old songs I heard when I was a kid, because they already were on the radio.”

The box set comes with 88 pages of amusing liner notes, some of which are anecdotes as well as temporal coincidences Stampfel noticed as he was working on them. In the note for his cover of Buddy Holly’s “Rave On,” he states, “What can I say about Buddy Holly? I once had a dream that I was back in 1959 trying to talk him out of taking the plane. In 1960, I also dreamed I was trying to talk Jimmie Rodgers into going into a TB treatment facility. He was in an expensive car and waved me off, just like Holly.”

In the liner note for Jimmy Jones’ “Handy Man,” Peter shares a story about working out a more manic version and playing it at the Gaslight Cafe in the Village when Bob Dylan was there. “That was the first time he heard the Holy Modal Rounders. When I told him our name, he said, ‘Holy Modal Rounders!?’ then said he had been thinking about giving himself a group name. He suggested I work out ‘Midnight Hour.’ Then he said, ‘I just wrote this new weird song’ and got up on stage and sang, ‘That’s All Right Ma, I’m Only Bleeding.’ “

Stampfel elaborates, “All these coincidences came up, like the fact that I was very discouraged musically in 1980, and because of all the groups falling apart. I like to play with people and I didn’t want to be a soloist. I was writing this exactly 40 years to the year after I started being a soloist because that was the only option. The last group effort I managed with this guy, John Parrott, fell apart in 1980. At the same time, my record company, Don Giovanni — not the company that does the hundred songs, but my regular record company — offered to release the tapes I made with the guy that I was in my last group with 40 years in the past.”

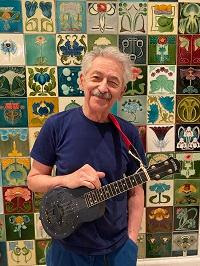

Working with a voice coach via Zoom has helped him to find useful aspects in a bad situation. “As well as she’s working with me on songs I’m working on and there’s lots of really good suggestions, like helping me find the right key to sing it in and taking a softer approach. She’s from the South side of Milwaukee, as well as me, which is really kind of an uncanny coincidence. And she went to Marquette university in Milwaukee. She’s a jazz singer and I’ve learned lots and lots of working with her, like doing more long notes for instance, like staccato. That was like an amazing thing that really changed how I sang. And I mentioned to Mark Bingham about singing long notes. And he said, ‘Oh, like Ella Fitzgerald.’ And it clicked. I’d never noticed that about her, but suddenly it was obvious.”

He wisely philosophizes that a breakdown is the best way to make a breakthrough. “Basically I’m learning technical stuff, which is really helping. The main exercise is lying flat on my back, which totally relaxes the body. I’m discovering all these tools and techniques I haven’t known about. Hopefully I’ll come out of it better than I was when I went in. Although there’s stuff I used to be able to do that I won’t be able to do anymore, that’d be a good trade-off, you know?”

20th Century is being released by Louisiana Red Hot Records February 5 as a 5-CD box set — digital download and via streaming platforms initially.

Pre-order 20th Century

*Feature image credit: Ebet Roberts/Redferns