Editor’s Note: Don Wilcock is currently writing his memoirs, looking back at 51 years starting with Sounds from The World, a column he wrote for “grunts” in the rice patties of Vietnam in what was then the largest official Army newspaper in the world, ‘The Army Reporter’.

Diabetes may have been Jerry Garcia’s official cause of death. Cynics may blame drugs, but based on my interviews with him and fellow Grateful Dead band mate Bob Weir, I feel it was his increasing inability to deal with the role of musical messiah in the minds of an ever-growing cadre of fans that numbered in the millions. For Jerry, it was always about his music, not about him.

Bob Weir was livid when I asked him in 2000 if Jerry ever got caught up in what people thought of him. Of course, I knew his answer, but I wanted to give Bob a chance to vent.

“No, almost never,” he answered. “For one thing, that is bullshit. That’s cult of personality bullshit taken to an absurd degree. Jerry despised that (said with poisonous precision). He hated it so bad that he used to hide from that. And he used the drugs to do that. That pretty much killed him, that cult of personality bullshit. That guy was pretty much my closest friend. I watched this. I watched it happen, and he hated it so bad, so much that he just – he hid from it. So, I just ignore it. First off, it’s not focused on me as heavily as it was on Jerry, but Jerry was quite human, I’m here to tell ya.

“He was very good one on one at dispelling that image pretty handily, but he was powerless to do it on a mass scale. It was just too much like work. I don’t pay much attention to it. It’s not focused as heavily (on me) as it was on Jerry. It’s not as much a problem. (But) you know I can’t walk down the street in certain places without causing a stir and having people – you know – adoring fans.

“You know there’s some gratification, but it’s awkward for me when I run into people who get all flustered and start shaking and stuff. I’m just a human being. And these people think they’re looking at something else they’re not seeing. They’re not even seeing what’s standing in front of them which is just a human being. They’re seeing something else, and that’s gotta bother you a little bit.”

Jerry told me in 1979, “We’re strictly working people, really. We’ve never been rich. I think that works out pretty well.” Understand the group was working on their 21st album in 14 years at that point in time. But although they were already a phenomenon equal in their fans’ eyes to Elvis or The Beatles in their impact on popular music, they were still fundamentally in debt. At that time, popular music acts toured to build a market for their albums rather than the other way around.

Not The Dead.

They were fundamentally a live band whose initial success was built around free outdoor concerts in San Francisco. They were performing the first of six shows at the Glens Falls Civic Center the last day in August, 1979, and Jerry was calling me to get publicity for that show. I missed his first call, and he actually called me back the next day. They still hadn’t finished the album, Go To Heaven. I’ve always wondered if that mini-tour wasn’t staged to raise enough money to stay in business. This from a band whose leader had recently told Features magazine “I can’t multiply fishes and turn water into wine.”

Jerry groaned when I quoted him on that. “Oh, my God. Did I say that?” John Lennon had caused a minor furor in the ’60s when he said The Beatles were more popular than Jesus. Jerry was already in denial of his messianic reputation in 1979. I asked him point blank if that were a problem.

“Luckily, not that many people confront me with it. If that’s true – and I really sort of doubt that’s true – I don’t have to confront that day after day. You know what I mean? People don’t often throw it in my face today. So, as long as I don’t have to live with it as a functioning dynamic in my life, it doesn’t really matter. It doesn’t have any bearing on what I do one way or another.”

So, you don’t have to insulate yourself, I asked.

“No, I don’t. I think it would be really uncomfortable if I did have to.”

But you mean a lot to an awful lot of people, I said.

“Uhm-hm. Well, luckily, though it’s – I would rather mean a lot to a relative minority which is the way our popularity is distributed. We sort of mean a lot to a few people in the big picture. I would rather have that than mean something to everybody like Johnny Carson or something, you know what I mean?

“I mean the way it is now, most of my life I don’t stand with a lot of attention being called to myself or that I’m famous or whatever. People once in a while come up to me and say, ‘I like your playing. I like your music and thanks for doing what you’ve been doing all of these years’ and things like that, and its usually very brief and friendly, and it doesn’t happen so often that I feel I have to go to great lengths to stay away from – to avoid people. You know what I mean?”

He even downplayed the role The Dead and their music had already played in changing the fundamental youth lifestyle. “I never felt like there was a whole generation or whatever that had music as a really, really important part of their, quote, lifestyle.”

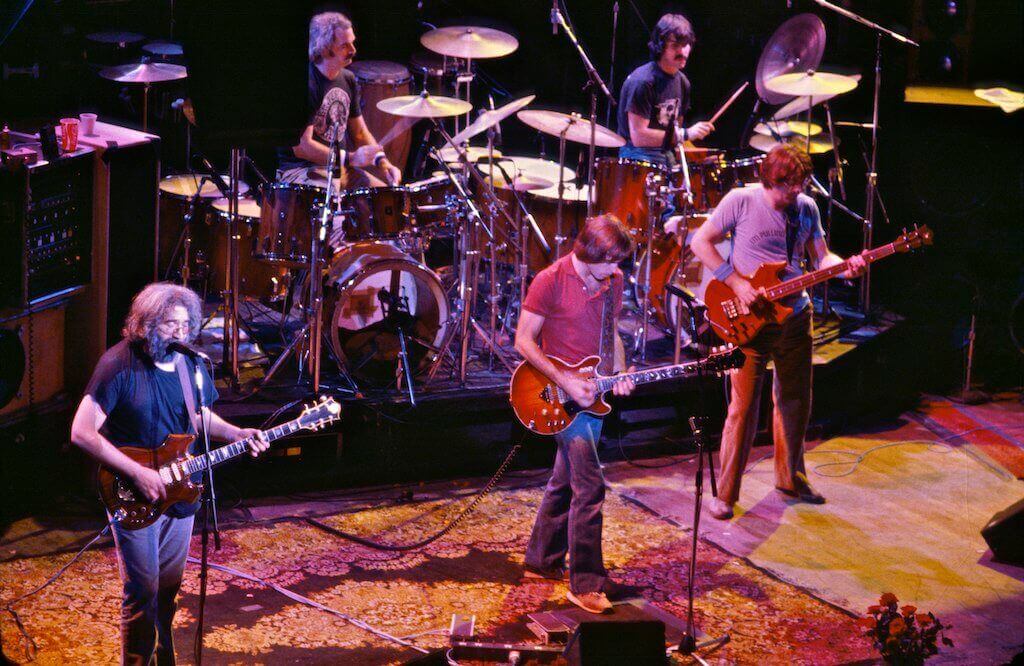

In my homage to him after his death in 1995, I wrote: “His fearless forays into over-the-edge experimentation were the single most important element influencing the wildly popular live Dead concerts. Thirty years after their first free concerts in San Francisco, the Grateful Dead remained clearly the number-one concert attraction and biggest annual draw, because Jerry’s kids could count on him to constantly evolve. No two concerts were ever alike. Not a single song in a three-hour concert would be played two nights in a row.”

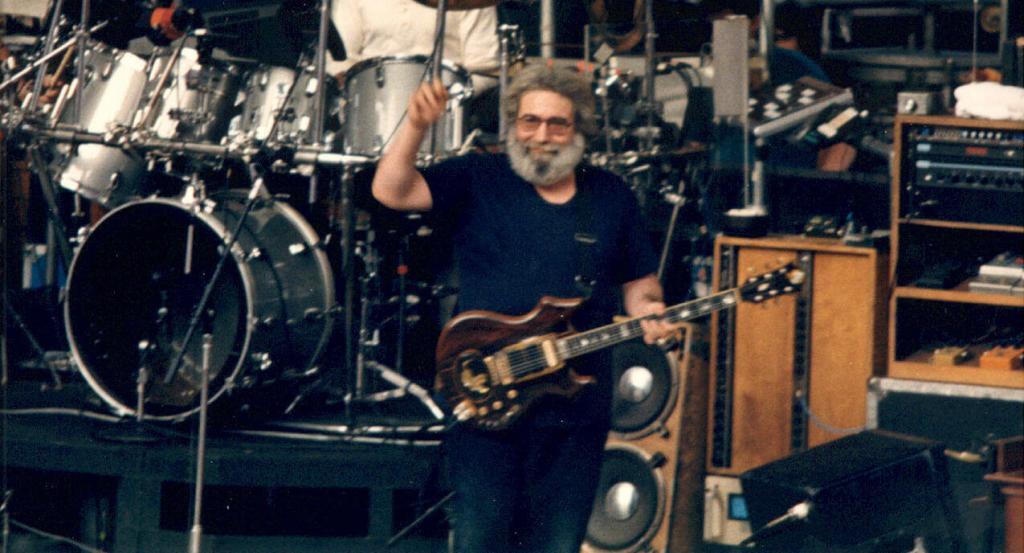

*Feature image by Mark L. Knowles licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.