The Animals’ We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and Country Joe and The Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die-Rag” are the two songs I most associate with Veterans Day. The first was by a British Invasion band, The Animals, and wasn’t written about wanting to leave Vietnam but rather by band leader Eric Burdon’s desire to get out of his hometown for London and then leaving London to find success in America. The second song was an antiwar song written by an Air Force veteran in the mid ’60s with the tag line: “One, two, three, four. What are we fighting for. I don’t give a damn. Next stop is Vietnam.”

Today, Thursday, November 11, 2021, is Veterans Day. As a Vietnam veteran I can score a free donut at my local Dunkin’ Donuts. Last weekend I introduced Sonya Ward at my stepdaughter Tanneal Green’s Fruit within Our Spirit benefit that featured my favorite gospel group The Heavenly Echoes. On her business card Sonya refers to herself as “founder and trainer” of Ibi Semper, an organization “engaging veterans and first responders with PTSD, improving lives and rescue shelter dogs to become PTSD Service Dogs and promoting awareness of PTSD.”

I got a round of applause and a couple of hoots in my introduction when I told the crowd that as a Vietnam veteran, I knew something about PTSD.

In 1969 when I came off active duty as a returning Vietnam soldier with Schenectady’s 1018 Army Reserve unit, I wouldn’t admit I’d been in the service. I couldn’t wait for my hair to grow long so no one would suspect I was a vet.

One of my high school classmates that I interviewed in 2012 for a film called Turning Pages told me she wouldn’t have considered dating a Vietnam vet back in the 1960s. Another friend, a three-time Purple Heart recipient and survivor of The Battle of Hue, was spat upon when he got off the plane from Nam in his uniform. Months later he attended the Woodstock Music Festival, parking his Harley under the stage, falling asleep and waking up to Richie Havens opening the festival.

With all the cultural changes we’ve gone through in the last half century from the Me, Too Movement to Black Lives Matters, none has moved the needle of extreme emotion for me more than the 180-degree shift in the attitudes towards veterans, at least among young people and music loves in general.

So, why do I think of those two songs on Veterans Day? The first one, “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” was the unofficial theme song for all who were caught up in the mandatory draft and sent to Vietnam. I worked nights in Army Headquarters editing The Morning World News Roundup.

Because of the strange hours I kept, I rarely got to eat meals in the mess hall. I usually began my long day’s night with a steak dinner, drinking a Jack and Ginger at the Non-commissioned Officer’s Club. I would watch the WACs and NCOs dance to the Filipino band of the day covering the current hit songs. These crack rock bands would end the night with “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.”

The song had gone to number 13 on the Billboard charts in 1965. It brought back memories of my college years and seeing The Animals in Boston. Decades later I got to talk to lead singer Eric Burdon about the lasting influence of that song on veterans of too many wars.

“That particular cut keeps re-incarnating itself,” said Burdon in 2013, “and it just never goes away. It first represented when I first sang about me wanting to get out of my hometown and go to London, and then get out of London and get to New York and then get out of New York and get to Los Angeles. Then, it kinda died down for a while. Then, I went back to Europe. I did some work raising money to build a hospital in the Soviet Afghanistan conflict, and it became the theme for that. It just goes on and on and on, you know?

“It’s definitely the soldier’s lament, that’s for sure. Every concert we get people saying, ‘It’s number one in Iraq.’ ‘It’s number one in Saudi.’ Yeah, it became a thing, and it goes all the way back to Nam. I get stories from guys who were in Nam. I could write a small book on it itself.

“It’s a rock song, but it has the value of being a pub sing-along thing. Everybody gets that line: “We gotta get out of this place,” and these days when I’m singing on stage, I just put the microphone out in the audiences to do it for me.”

Burdon once visited the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington D.C. with actress Angie Dickenson at 2 in the morning. As they walked up to the long shiny black wall, they encountered a group of vets sitting before the monolith. Beside them was a tape player. The music that filled the still night air was by The Animals.

“They just had the tape that probably had been with them in the dust-up (Vietnam conflict), you know. It was caked with mud and stuff like old fashioned Japanese tape machines. It just happened to be spinning with other songs on there. I said, ‘Wow, that was freaky,’ because they were sitting cross-legged in front of the wall.

“That was great of Angie to do that. She was really a gracious woman. She took me around to all of the Washington monuments and everything at 2 o’clock in the morning. Yeah, that was great, a part of history, American history – and I have to say somewhat erotic.” [Chuckle]

Erotic!?

“Well, you know, when Angie’s wearing the same McIntosh she wore in the great murder movie she did – I forgot what it was called – and her well-manicured fingernails were going along the black surface of the wall looking for a name. It was cool. It was very cool, and I can’t thank her enough for taking me on that trip because otherwise I probably never would have made it.”

The second song, Country Joe McDonald and The Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” captured the anger of a generation caught in the net of a war their fathers and the politicians of the day saw as a way to stop the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia.

Well, come on all of you, big strong men,

Uncle Sam needs your help again.

He’s got himself in a terrible jam

Way down yonder in Vietnam

So put down your books and pick up a gun,

We’re gonna have a whole lotta fun.

And it’s one, two, three,

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn,

Next stop is Vietnam;

And it’s five, six, seven,

Open up the pearly gates,

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why,

Whoopee! we’re all gonna die.

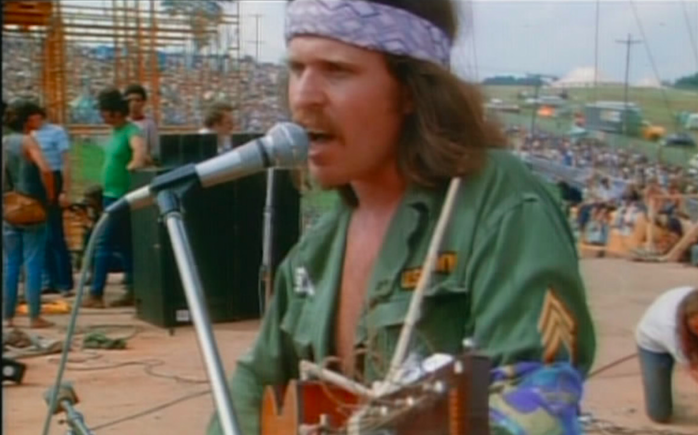

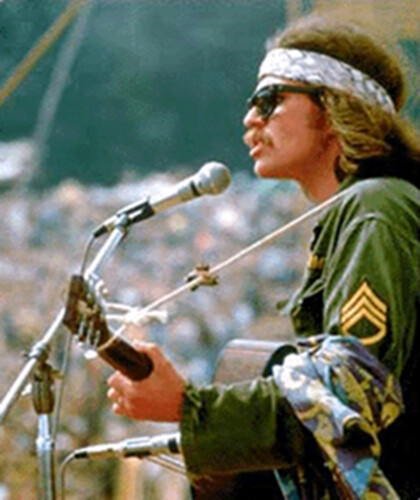

The group sang the song at Woodstock in 1969 when I was in Vietnam. Country Joe McDonald had been in the Navy Air Force in Japan from 1959 to ’62.

“I never dreamed that song would become so popular,” McDonald told me in 1988. “Most people from the anti-war movement who are not vets think the song is putting down soldiers, but it’s not, really, and I never had that intention in mind when I did the song. I’m glad the song went where it did and seemed to be a morale booster to people working against the war and for people fighting in the war, too. I never thought the soldiers were to blame for what was happening in Vietnam. I never thought the soldiers were evil and bad.”

In my “Sounds from the World” column that I wrote for The Army Reporter in Vietnam, I often felt like the wolf in the chicken coop with my anti-war sentiment, and I never did write about Country Joe and the Fish there. The words to “The Fish Cheer” just seemed to be too close to poking sticks at the animals.

Today, when I tell people I’m a veteran, I get these empathetic looks, a kind of crooked smile, and they universally say, “Thank you for your service.” Those five words bring on such mixed emotions more than five decades later, and I wonder if those who say it have any idea what soldiers really go through.